|

The student union at Iowa State University has held a special place in the memories of three generations of students. Since its construction in 1928 and eleven subsequent additions, the Memorial Union has made its Great Hall available as the premier venue for student gatherings on campus. The expansive two-story, 54 x 100 ft. room features vintage carved ceiling beams, stained glass light fixtures, dark oak paneling and durable hard-maple flooring. Here, students have participated in an array of social activities: dances, convocations, banquets, concerts, lectures, exhibitions, film showings, orientations, reunions and madrigal dinners. More than a few couples have met at dances, become engaged and later married. To commemorate such an instance, successful alum, Charles Durham, donated funds in 2008 for restoring the Great Hall. In fact, the hall now bears the names of Charles and Margre Durham in recognition of his gift. The pipe organ has shared an important role at many events, beginning in 1936 and continuing for the next 60 years. Students attending Iowa State in the late 1930s through the 1950s have especially fond recollections of hearing this organ played. Sometimes it was used on-stage with dance bands, other times for noontime concerts, silent films, radio broadcasts, receptions and even memorial and worship services. The organ’s sonorous tones completely engulfed the hall and reverberated for many seconds in the lively acoustics. Although the bulky, three-manual console was sometimes viewable onstage, the sound-producing components of the organ, over 1,400 pipes, remained hidden behind two symmetrical, arched grills at the west-end of the hall. Listeners were assuredly aware of the sound source when the organ was being played. Being located in the center of the Union, the organ made its presence known to occupants in the Gallery and Pioneer Room as well as adjoining conference rooms. Overnight patrons of the second-floor guestrooms frequently became unwilling listeners as they attempted to slumber while subject to the low rumblings of the pedal pipes. It was often joked that lingering users of the adjacent men’s room were assisted in their efforts by the palpable vibrations emanating from the low octaves. SOURCEWhen the Great Hall was built, two chambers for a future pipe organ were included in the design, one on each side of the stage. That organ didn't materialize until eight years later through a gift of two alumni of the class of 1910. As Harold E. Pride, former director, relates in his history of the Memorial Union, W.I. Griffith, director of WOI radio station, heard in 1935 that an organ was available for purchase from a theater in Madison, Wisconsin. Research reveals that this was the 1,300-seat Parkway Theatre, which started out as the Fuller Opera House in 1890, and was remodeled in 1921 for use as a legitimate theater and movie house. After a stage fire damaged the original organ, a new Barton theatre organ was installed in 1926. This instrument was organ number 190 built by Dan Barton’s Bartola Musical Instrument Company of Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The organ was classed as a “Butterfield Special,” a series of three-manual/eleven-rank, economy organs built mainly for the Butterfield Theater Chain that operated in Michigan. Parkway Theatre received less than ten year's use of their new Barton organ before it was placed in storage after the introduction of the "talkies." Dan Barton was one of the top five suppliers of organs to theaters in the silent era, and built 250 theatre organs from about 1918 to 1931. His most famous installation was the 6/51 Chicago Stadium organ of 1929 boasting over 3,000 pipes. DONORSIn the spring of 1936, Harold Pride passed on knowledge of this organ and the need for one in Great Hall to Wilfred G. "Bill" Lane who was visiting campus and prepared to present a sizable check to Iowa State. In 1932, this engineer had entered partnership with classmate Walter T. "Prep" Wells in the Lane-Wells Company that took over the old Pacific Oil Tool Company of Los Angeles, specializing and developing technical oil field services. Their first success was the invention of a gun perforator to pierce holes in oil well steel casings and cement liners to increase oil flow. This device proved to be a significant contribution to production in over 30,000 oil wells in the U.S. Their successful venture launched a series of gifts to the university beginning with their 25th class reunion. Later gifts included the memorial entrance gate to Clyde Williams Field, completion of the fourth and fifth floors of the Memorial Union, land for the college golf course clubhouse, and scholarships in Engineering and English. When told of the bargain price of the organ in Madison and shown the chambers that the architect had provided in the Great Hall, Lane immediately became interested, especially since he was himself an organ music buff and organist. After phoning his partner "Prep" Wells in California, he told Director Pride to "go ahead and buy that box of whistles, Walter and I will pay for it." The organ was valued at $18,000 at the time of its installation.

Dedication

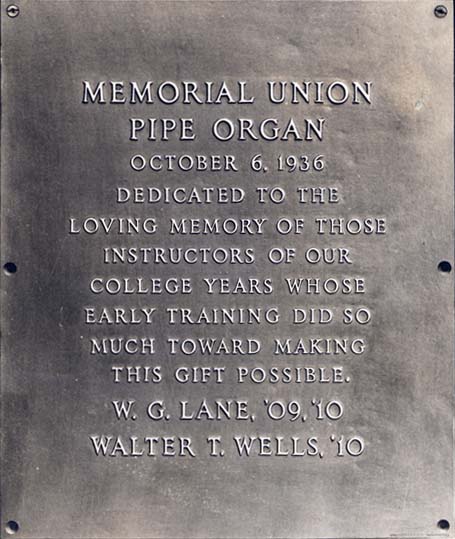

program, 1936 (click for larger version) DEDICATIONEmployees of the Physical Plant drove a truck to Madison to pick up the organ from a warehouse where it had been stored. Once back in Ames, all pipes and parts were laid out on the floor of Great Hall that was closed to the public throughout the summer of 1936. Finally, on the 6th of October the organ was ready, and a dedicatory recital was played by Frederick Fuller, music director of University of Wisconsin radio station WHA in Madison. As an accomplished organ performer, Fuller knew how to showcase the resources of the instrument, and delighted over 1,000 people packed into the Great Hall. The secret donors were announced by their former teacher, Dean Maria Roberts, and presented to the audience. Bill Lane dedicated the organ "to the loving memory of those instructors of our college years whose early training did much toward making this gift possible." A bronze plaque set into the oak paneling to the right of the stage preserved this statement for posterity. Wilfred Lane retired in 1938 and died in 1949, while Walter Wells continued as Chairman of the Board of Directors of their corporation and remained active in charities until his death in 1964. ORGANISTSH. Frederick Fuller originally came from Chicago where he followed a musical career as had his father, Henry Frederick Fuller, an organist and student of Sir John Stainer in London. He entered radio in its infancy, broadcasting features regularly over Midwestern stations. Besides performing, Fuller also taught organ and did maintenance for church, theater, radio and concert hall organs as well as planning and installing area organs. After World War II he operated an organ business for ten years, using the name Maxcy-Barton. As WHA musical director he planned and wrote scripts for "Music of the Masters," an eight-week "Music Appreciation" course, and "The Noon Musical," a dinner program of salon and chamber music. His church post in Madison was as organist and choirmaster at St. Andrew's Episcopal Church. While in Ames, Fuller played over WOI radio two days after the dedication following the inauguration of President Charles E. Friley. Later that same week, Howard Chase (1909-1981) of the ISC Music Department was appointed official organist of the Memorial Union Barton, and began daily noontime recitals of semi-popular and classical selections from 12:30 to 1:00. Chase, a graduate of Des Moines East High School in 1927, studied organ shortly thereafter with well-known theatre organist and teacher Henry Francis Parks of the Chicago Musical College. While in Chicago, he served as assistant organist at the Evangelical Lutheran Church and substitute organist at the United Artist Theater. At age 19 he was regular organist at the Circle Theatre in Nevada from its opening on October 17, 1928. Chase continued his musical study at Drake University and at Juilliard under Hugh Porter. In Ames, he was also organist at the First Baptist Church from 1927 to the 1940s. For his daily concerts in the Great Hall, Chase devised a system whereby a person walking into the hall at anytime during the noon hour could know what selection was being played. The recital program for the day was posted on a large bulletin board, with each selection numbered to correspond with numbered cards displayed at the on-stage organ console. In 1939, Wednesdays featured selections programmed by Chase, and Fridays were devoted to selections left in a request box at the main desk. Besides the noon-day programs, Chase played for vesper services, twilight musicales, parties, receptions, Varieties, four commencements a year, and broadcasts over WOI. He also broadcast from the 1936 Kilgen theatre organ at radio station WHO in Des Moines. In addition to giving piano and organ lessons, teaching music appreciation, and serving as Memorial Union organist, he was music supervisor at WOI Radio and started the classical record library there. Mr. Chase took a year's leave to earn his master's degree in music theory from the University of Michigan during 1944, and left Iowa State in 1946 to become instructor in music theory at Ann Arbor. The last 25 years of his career were spent at the University of Nevada, where he started the music department. In appreciation for his many contributions there, the library's music listening room was named in his honor.

TRANSFORMATIONThroughout its history, the organ has been in a continual state of modification. In the early years the Music Department insisted on making it less theatrical. At some point, the percussions (tambourine, castanets, Chinese block, tom-tom, cymbal, drums and thunder effect) were all removed. P.J. Buch (pronounced Bush), a Cedar Rapids technician who serviced the organ at the time, was asked to remove the Kinura rank, whose buzzy sounding pipes were considered offensive to classically trained ears. Pete obliged and surpassed his charge by giving away the pipes to children for use as Halloween horns. The console did not escape the classical transformation either. Its graceful scalloped lid, molded compo candelabra decorations, and textured plastered panels were removed and replaced with a plain, dark oak shell to match the paneling of the Great Hall. Since at least 1939, Howard Chase had harbored a desire to add ranks to the Barton despite objections from the original donors. In October 1943 he learned of an organ for sale through P.J. Buch. The organ in question was a ten-rank theatre organ installed early in 1926 in Iowa City's Pastime Theatre by Otto Solle of Chicago. It featured a Musette rank and an unusually complete set of percussions including Parsifal bells and tuned sleigh bells, none of which were common in small installations. In all probability this was an organ assembled from parts to satisfy the economy-minded theater owner. This instrument was available for purchase at the very reasonable price of $850. It was pointed out at the time, that the 20-note cathedral chime (to replace the original 13-note Barton one) and the 37-note celeste harp were worth that money alone. In 1944, the 13-note chime was passed on to the First Christian Church in Ames where it was used until the year 2000. Before Mr. Chase left on a year's leave, he examined the instrument and recommended its purchase. Installation in the north chamber ran the total costs up to $2,860. In the process of doubling the number of ranks, existing pipes in the north chamber were moved to the south chamber. Returning from Ann Arbor, Michigan for a few days, Howard Chase had scheduled a special recital for October 22, 1944 to celebrate the reconditioned organ. However, wartime shortages of labor and scarcity of materials made it impossible to complete the work in time, and the recital had to be canceled. During the 1940s the organ was regularly used for Faculty Women's Club programs and for Sunday services broadcast over WOI Radio. Two technicians maintained the organ during this period: Robert Beeston and Robert Milliman, both of Des Moines. Ralph Borck, a recently hired WOI-TV studio producer, began his long association with the instrument in 1951. He received undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of Iowa in Speech and Theater. Upon his arrival in Ames, he discovered the Barton organ in the Great Hall. In spite of his lack of understanding of organ building, he serviced, tuned, added and substituted ranks to the organ for the next 43 years. With the organ as his hobby, Mr. Borck worked on his own time using shop mechanics and students employed by the Union to assist him. The first major addition was in 1969 with ranks of pipes salvaged from the Des Moines Theater just before it was razed. This theater formerly stood at the corner of 6th and Grand next to the Paramount in the capitol city, and possessed a 1919 Kimball organ with an Echo division in the third balcony. Even though all the "traps" had been long since scavenged by children, the pneumatic actions were saved and moved along with the pipes and pedal windchests to Ames. Most of the ranks added in 1944 were removed to make room for the Kimball ranks. The Music Department used the organ as a teaching, practice and recital instrument from the late 1930s through the 1960s. Because classical organists were confused by the console layout of a theatre organ, the Department had the wiring of the top and bottom manuals switched. Late one night in 1956 or 1957, Ralph Borck and Paul Buegel, another WOI employee, switched the manuals back to their original positions much to the shock and confusion of the female organist who came in to play it the next day. The Department never did know who perpetrated the deed. Accomplice Paul Buegel, who first discovered the organ as a student in 1948, was a theatre organ enthusiast who enjoyed playing and servicing the organ throughout his stay in Ames. He was later hired by Ralph Borck to assist in the WOI studio. Besides working on the mechanics of the Union organ, Mr. Borck regularly presided at the console for university functions during the 1960s and 1970s. Ralph began music studies by first taking piano lessons. Then during high school in the 1930s, he learned theatre organ technique from theatre organist Don Miller. Lessons were taken on the three-manual Wurlitzer at the Great Lakes Theatre in Detroit. Through the years, many faculty, staff, students and visitors heard Ralph play during noon hours, at alumni banquets, and other occasions. In 1971, Mr. Borck moved the console from the stage to the north balcony using considerable muscle power provided by “volunteered” shop employees. This rather drastic relocation necessitated the removal of the pneumatic stop action in the console, since a lengthy flexible windline from the blower in the basement to the balcony was no longer feasible. As a further consequence the combination action was also disabled. During the summer of 1988, Tammy Swenson, a Computer Science major and craft hobbyist, assisted Ralph by hand painting a carved wood molding decorating the console, releathering pouches, and installing a heater in the east chamber. The last major addition came during 1979-1980 with the incorporation of twelve ranks of pipes from the 1929 M.P. Möller organ in Westminster Presbyterian Church at 4114 Allison Ave. in Des Moines. After removal by Ralph and Paul, nine of the ranks were installed in a newly created Echo chamber in the east balcony where a separate Kinetic blower provided wind pressure. Student assistants Mark Turner and Mike King were indispensable in helping with this installation, staying on to help Ralph between classes, on weekends and during vacations to repair, releather, tune, etc. Mike's tenure from January 1979 to 1985 also allowed him to gain experience setting up for the annual Madrigal Dinner and Varieties performances.DECLINEBy the 1990s, the organ could have been described as a Barton hybrid totaling 21 ranks of pipes in unplayable condition and in need of extensive renovation. Ironically, had the organ been left unmodified with only routine tuning and servicing through the years, it could still be functional today. In the fall of 1995, the Union began a series of major renovation projects. Installation of a long-overdue separate air-handling system for the Great Hall dictated the permanent removal of the Echo division. The contract for the removal of the Echo’s Möller ranks went to Dennis Wendell, an ISU faculty member, longtime friend of Borck and organist/pipe organ “recycler.” Various church organ projects were the eventual recipients of these ranks. Renovation of the basement Commons area required expansion into the area occupied by the five-horsepower, 1200-pound Spencer Turbine blower. After furnishing a stable wind supply for sixty years, it was removed in November and placed in storage awaiting future renovation of the instrument. Sometime later, the original relay was removed from its room backstage and discarded. Ralph retired from the university in June of 1994 and died four years later, thus ending his long association with the Union's pipe organ. It had always been his vision to see the organ renovated and regularly used. To further this end, and to ensure a legacy, he left a portion of his estate “to be used to defray the costs of tuning and maintaining the pipe organ located in the Great Hall of the Memorial Union and subject to the responsibility of the Director of the Memorial Union to make the pipe organ available to interested organists for practice at reasonable times when the Great Hall is not being used by others.” The Memorial Union accepted the bequest in June of 1999 after obtaining an estimate of organ renovation costs, and the organ renovation project was included in the Five-Year Capital Plan. During 2001 and 2002, the Union began exploring a major renovation of its building. The Memorial Union had operated on the ISU campus for 75 years as a private, non-profit corporation. Its intentions, once its debts were paid off, were always to turn its assets over to the university. On November 18, 2002, the Union entered into an agreement with the Board of Regents, State of Iowa, to transfer its assets and liabilities to the Board for use by Iowa State University.DISPOSITIONAs the last item of business before dissolution of the Union corporation, the fate of the organ and the Borck bequest had to be resolved. Memorial Union officials, who had been seriously reconsidering the situation of the organ during that fall, determined that the organ no longer fit their needs, and the Board of Directors voted on January 31, 2003 to dispose of the organ. The university assumed ownership of the instrument as part of the transfer of the Union’s property on March 31, 2003, and later agreed to donate the organ to an appropriate charitable organization. In proceedings of the Iowa District Court for Story County relating to the reopening of the Ralph Borck estate, the court approved, in January 2004, the disposition of the organ bequest to a new recipient according to the legal doctrine of “cy pres.” Again, Dennis Wendell, now a retired ISU emeritus faculty member, appeared on the scene. With encouragement from the Memorial Union, ISU President Gregory Geoffroy, and Don Newbrough, executor of the Ralph Borck estate, Wendell launched a nine-month search for an appropriate new home for the organ. Required selection criteria established by an ad hoc organ committee were: a non-profit 501(c)(3) public venue; restoration, tuning, maintenance; availability for practice; adequate space (organ chambers and audience seating); fund accountability (periodic reports); and removal by recipient. Preferred criteria specified a high-profile central Iowa location; knowledgeable technician familiar with theatre organ installation; and active programming and/or educational component to enhance theatre organ appreciation (film showings, concerts). The new venue approved by the university turned out to be only 45 minutes travel south to Hoyt Sherman Place, a historic house museum and performing arts center in Des Moines. Their 1,400-seat theater addition built in 1923 was recently renovated at a cost of $5.5 million. Re-opened in 2003, the interior is dominated by rococo plasterwork of hundreds of rosettes on the domed ceiling showcased by fresh gold paint, appropriate period colors and dramatic lighting. The excellent acoustics and lavish décor of Hoyt Sherman Place seemed ideal for the Barton organ. The only problem was that a Kimball pipe organ already occupied the existing organ chambers. Donated in 1937 by Carrie M. Hawley as a memorial to her husband, Henry B. Hawley, that organ was not designed for theatrical use, and never adequately provided the exciting complement needed for diverse events. With approval from the Hoyt Sherman Place Foundation Board of Directors, the Kimball was offered free to an organization willing to provide a new home and move it. On February 26, 2004, about $144,000 from the Borck estate was transferred to Hoyt Sherman Place Foundation, and on November 29, a contract to renovate and install the Barton was signed with Robb Kendall, a pipe organ technician based in Galena, Illinois. In December 2004, Robb oversaw removal of the Barton from the Great Hall and placement into temporary storage. After helping to find a new home for the Hoyt Sherman Kimball, he proceeded to prepare the two vacated organ chambers and refurbish and install the Spencer blower in an attic room above the stage. Progress was slow during the next four years as swell shades were refurbished, percussions and sound effects restored, console readied, stop tabs engraved, pipes cleaned, and wind chests refinished. Work completely ceased at Robb’s untimely death on March 10, 2009. With an incomplete instrument and enthusiasm and financing for the project lagging, the Foundation voted to abandon the organ installation. The components and remaining funds were offered to the Pella Opera House with the understanding that they would be used to enhance and maintain the 3/12 Barton previously installed by Robb and premiered in 1995. This instrument remains in regular use and is made available to organists wishing to practice on an authentic theatre organ. Transfer began on November 5, 2011. Thus, the legacy of the original donors, Bill Lane and Walter Wells, promises to continue albeit in a new venue. Playable, vintage theatre organs are not common. Surviving examples available to the public in Iowa include: a 3/12 Wurlitzer in Paramount Theatre, Cedar Rapids [console damaged in the flood of 2008]; a 3/14 Barton in the Community Theatre, formerly the Iowa Theatre, Cedar Rapids [console also damaged in the flood of 2008]; a 3/12 Wicks in Capitol Theatre, Davenport [in storage]; a 3/12 Barton in the restored Opera House, Pella; and a 3/13 Wurlitzer in the Municipal Auditorium, Sioux City. November 1995; revised: June 1999, Sept. 2003, Sept. 2008, Dec. 2011.

Sources

Barton Archives. Oshkosh Public Museum, Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The Bomb (ISU yearbook) 1938, p. 186. Buegel, Paul. Telephone conversations, November 1994 - May 1995. Chase, Howard. File, Dept. of Music Personnel Records, RS 13/17/2, box 1 Fladen, Jerry. Telephone conversation with Madison theater historian, April 18, 1995. Friley, Charles E. Papers (unprocessed) RS 219/3, University Archives, Iowa State University Library. Correspondence between ISU president and Tolbert MacRae, Head of Music Dept., 1939, 1943-1944. Iowa City Press-Citizen, January 29, 1926: "Pastime Theater's famous organ now ready for use" Iowa State Student, September 19; October 3, 6, 8, 10, 17, 22; November 7, 1936; October 17 & 20, 1944. Junchen, David. Encyclopedia of the American Theatre Organ, v. 1, pp. 88, 416. Kendall, Robb. Editorial contributions, 1995-2005. King, Mike. Interview, November 1995. Memorial Union Records, RS 21/5/1, University Archives, Iowa State University Library. Parkway Theatre photographs (exterior), Visual and Sound Archives, Wisconsin State Historical Society, Madison, Wisconsin. Parkway Theatre photographs (interior), Historic Photo Service, Madison, Wisconsin. Parkway Theatre photograph (Bob Coe at console, 1926 opening), Duane Austin collection. Pride, Harold E. The First Fifty Years, Iowa State Memorial Union. Crystal Lake, Ill. : P.P. & J.A. Smith, Scott. “The Butterfield Specials.” Theatre Organ, January/February 2003, pp.70-79. Swenson, Tammy. Interview, November 1995. Turner, Mark. Interview, November 1994. Wendell, Dennis. Memorial Union Pipe Organ File, 1926-2008. |