"… [T]he climax of dissent, disruption, and tragedy, in all American history to date occurred in May 1970. That month saw the involvement of students and institutions in protests in greater number than ever before in history" (Peterson & Bilorusky, 1971, p. xi).

POLITICAL PROTESTS

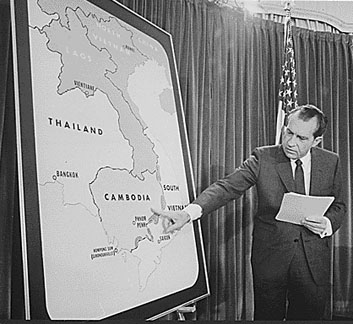

On the evening of April 30, 1970, in a televised address to the nation, Richard M. Nixon, the thirty-seventh President of the United States (see Figures 1 and 2), announced an imminent attack against "major enemy sanctuaries on the Cambodian-Vietnam border (WGBH, 1997)."

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figures 1 and 2. Richard Milhous Nixon, President of

the United States of America,

1969-1974.

Commonly referred to as the 'Cambodian Invasion', the incursion was deemed necessary to destroy Communist bases and supply lines supporting the war in Vietnam, to protect American servicemen and women, and to guarantee the successful withdrawal of America from Vietnam (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Nixon announcing the invasion of Cambodia in a televised address to the nation.

By the end of the speech, students on college and university campuses across the United States, and elsewhere, gathered and called for mass meetings to plan to protest an action considered by many as an escalation of an increasingly unpopular war.

"People on the campuses who opposed the Vietnam War felt that the President had deceived them, that the hated war, instead of being wound down, was to be expanded" (Peterson & Bilorusky, 1971, p. 2). "Princeton, Rutgers, and Oberlin mounted demonstrations that very night. Within three days, calls for massive nationwide demonstrations came from Yale May Day spokesmen, the National Student Association, the Student Mobilization Committee, and the then recently disbanded Vietnam Moratorium Committee. A National Student Strike Information Center was set up at Brandeis University, which by May 5 was reporting that 135 colleges had closed" (Peterson & Bilorusky, 1971, p. 2).

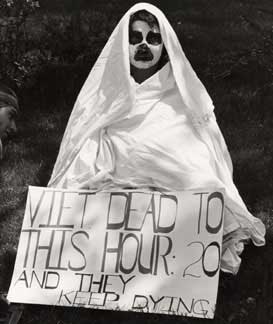

Figure 4. One of many who protested the Vietnam War and the Cambodian Invasion.

"Expressions of protest across the country took every conceivable form and were carried out under every conceivable banner, slogan and cry (see Figure 4). There were strikes, boycotts, and shutdowns; there were marches, rallies, and campuswide convocations; there were flag-lowerings, black armbands, memorial services, vigils, and symbolic funerals; there were special seminars, teach-ins, workshops, and research projects. There were students talking to residents in their homes and where they worked, and there were invitations to the public to come to the campus to talk" Peterson & Bilorusky, 1971, p. 4).

"For hundreds of thousands, even millions, of students, faculty, and staff at more than half of the nation’s colleges, 'business-as-usual’ became unthinkable. It was a mass uprising, embracing many more ‘moderate’ than ‘radical’ students; in consequence, the protests were overwhelmingly peaceful and legal, though by no means invariably so" (Peterson & Bilorusky, 1971, p. 1).

Iowa State students, "usually considered as conservative and apathetic," were among the many worldwide to react to the invasion (Bomb, 1971, p. 42).